--Type Title Here--

DICKEY FAMILY FINDS SPECIAL MEETING PLACE

By David Williams

September 16, 2004

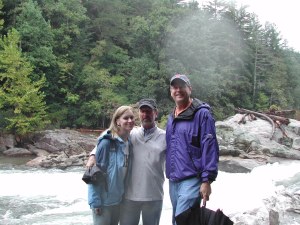

LONG CREEK — Family reunions are common in Oconee County, but Thursday’s gathering of the three children of author James Dickey on a rock overlooking the Bull Sluice rapid on the Chattooga River may be one of the most uncommon family gatherings ever in the county.

It was Mr. Dickey’s novel and later the movie "Deliverance" that brought national and world acclaim to the wild and scenic river and to Oconee County, which had no whitewater rafting companies when the film finished shooting in 1971....

Links to sites devoted to James Dickey:

Latest James Dickey publications:

A collection of articles in the Free Times of Columbia SC:

------------------------------------------

Kevin's work as one of America's leading interventional radiologists is well reported in medical journals, but less accessible on the open Web. Fortunately there are a few articles that explain his work to the general public, including one on aneurysms.

------------------------------------------

Bronwen's column in Newsweek, March 1997:

MY TURN

HE CAUGHT THE DREAM

HE CAUGHT THE DREAM

MY FATHER WAS MY MENTOR AND THE DOMINANT FORCE IN MY LIFE. I GRIEVE FOR HIM

EVERY DAY.

And if the earthly has

forgotten thee,

Say to the silent, "I am

living."

To the running water,

say "I am." -- Rainer Maria Rilke

MY FATHER ALWAYS SAID THAT WHEN it comes to writing, write what you want to

say. The questioning, the changing, the editing ... that all comes later.

"Use the freedom," he said. I have just watched my father die. His life,

which was reduced in the end to pulses on a dusty screen, has ended. And, if

I can find the strength, this is what I want to say.

You could say that the day had been a tough one. As much as the grieving

family tried to prepare me, I was horrified by what I saw waiting at the

hospital. I did not recognize the man before me. That man was not talkative

and vibrant. That man was not determined and strong. That man had given up.

And, perhaps, it was time to. He was nothing more than a pained skeleton,

and his chest heaved as though every breath was a last valiant effort. His

fingers were purple from lack of oxygen, though it was being forced into his

lungs in liters. My father was not physically recognizable, but his essence

was still strong in the room. His books were strategically arranged nearby,

and he still wore two watches, his Citizen Wingman and his Ironman

Triathlon. Funny, he always had to be on time.

I can't remember exactly what I said to him- I think I was talking about

boys and school and other trivia-but I remember him looking up at me through

all the tubes and the plastic with tears in his eyes. He did not have the

strength to cry, but I think he knew it would be the last time we saw each

other. All I could do was burst into tears and flee from the room. Here was

the man that changed my diapers, made me peanut-butter sandwiches (with the

crusts cut off), showed me how to throw knives and to shoot a bow, read me

poetry, stayed up with me all night when I was sick, taught me to play

chess, came to all my recitals, braided my hair, watched movies with me,

checked my homework ... and he was dying. Dying. And where was the pride in

his death? Where was the glory in being the human part of an oxygen tank?

I forced myself to stop the tears and returned to the room. I sat down in

the chair beside his bed and held his hand, which was covered in a mix of

blood and Betadine from the IVs. "Come on, Dad," I tried to say with a

smile. "I need you, OK?" And what he said, the last words he ever said to

me, were "I've always needed you." God, I loved my father. I squeezed his

hand and told him that I loved him, and he nodded. Weary and dazed, I left

the hospital with the hope that he would just hold on through the night, but

he couldn't.

I was awakened at 11:18 p.m., Sunday, Jan. 19, with the news that my father

had died. In a way, it was a relief. I didn't want him to hurt anymore. He

should have been paddling down some wild river in a canoe, or playing

bluegrass ballads on his guitar, or tapping away at a typewriter, not

straining for breath in some sterile hospital room. I got dressed and drove

to the hospital with no tears, and I saw that the door to his room was

partially open. Seeing the person you love more than anything in the world

dead is one of those lose-lose situations. I figured I either would see him

that last time and have that image burned into my memory forever, or I would

always wonder and wish I had. My father told me never to look at him dead,

and I should have listened. It was the most horrible thing I have ever seen.

I never thought there could be such a dramatic difference in a person who is

very ill and one who's dead, but the difference was incredible. The lights

were off, and there was an eerie backlight behind the bed. My father... My

father's body was 'propped up, but his head had fallen back and his mouth

was open. He looked like he was in pain. A lot of pain. Did I have to see

him gasping for air the last time I ever saw him? I screamed. I didn't know

what else to do. I just stood there in hysterics. The only person with me

was my brother, Kevin. He didn't know what to do, either. We were both kind

of floating around in a sea of turmoil and pain. I am still in that sea.

There are islands of normality and "okay-ness," but the existence of the

islands does not destroy the existence of the water.

There was no time for grieving that week. There was too much to do. Funeral

and memorial-service arrangements, cleaning out the house (which we had to

sell), appraising most of the big items in the house (which we had to sell),

changing locks so our house wouldn't get looted, those sorts of things. And

then we had to deal with all the fans and the sycophants. I don't remember

when I really did grieve. I think I do every day, because every day I am

overwhelmed with ire fact that I will never see him, talk to him, ask him

questions or listen to the answers again. He was my mentor and the dominant

force in my life.

So I am left with memories of greatness. Not the greatness of the writer but

the greatness of the father and the teacher. One time in the class he

taught, my father was reading his poem "Good-bye to Big Daddy," about the

death of football player Big Daddy Lipscomb, and this big ox-headed football

player in the class started bawling in the middle of the reading. The class

was dismissed, and my dad just went over to this guy and held him while he

wept like a child, saying, "It's all right, Big Boy; it's gonna be OK." That

is the kind of teacher James Dickey was. There are no words for the kind of

father he was.

A few of his favorite quotes echo through my mind like steps down an empty

hallway. "Live blindly and upon the hour" from a sonnet by Trumbull

Stickney; "None of them knew the color of the sky," the opening line of

Stephen Crane's "The Open Boat"; "Catch thou the dream in flight," and a

line referring to someone's eyes that were,''somewhat strangely more than

blue."

I will live blindly and upon the hour. I will catch the dream in flight,

though I do not know the color of the sky. And my father's eyes, though they

will not see my graduation, my marriage or my children, will always be

somewhat strangely more than blue.

-------------

DICKEY, 15, is the daughter of the poet and novelist James Dickey, who died

this year at the age of 75.

---------------

Links to Tom Dickey

Our old house in Leesburg, which now seems to be a conference center:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

And still more family ...

----------------------------------------------------------------------

More on James Dickey

More on James Dickey

Reviewer: Earl R. Bradley from USA

I was Jim's pilot in WWII and was astounded by some of his "recollections", but, then, does an auther have to (or should he) tell the truth? His job is creating images.